LunarDeltaT

Fangzheng Liu, Kerri Cahoy, Ariel Ekblaw, and Joseph A Paradiso.

"A Wireless Lunar Sensor Node Powered by Temperature Gradients across the Device's Surface".

In The 45th international IEEE Aerospace Conference (2024).

[PDF]

Overview

Miniature ballistically-deployed wireless sensor nodes can extend the exploration

of rovers and landers to hard-to-reach or dangerous areas

(e.g., rock piles, steep crater rims, etc.)

on the Lunar surface. After deployment, multiple sensor nodes can collect simultaneous

data from different positions, which aids in studying dynamic phenomena.

To guarantee long-term operations, energy harvesting is crucial.

When a miniature wireless sensor node is deployed on the Lunar surface,

one side will face the sunlight and the opposite will be in shadow.

The moon's surface is essentially a vacuum, hence the temperature on the sunlit

side is much higher than the shadowed side due to the lack of an atmosphere

to block solar irradiation in the sunlit areas and trap heat in the shadowed areas.

This can form a large temperature gradient on the sensor node surface.

I studied this in-situ energy harvesting approach by using a

custom thermopile that leveraged the temperature gradient between the sunlit

and shadowed sides of the sensor node's body.

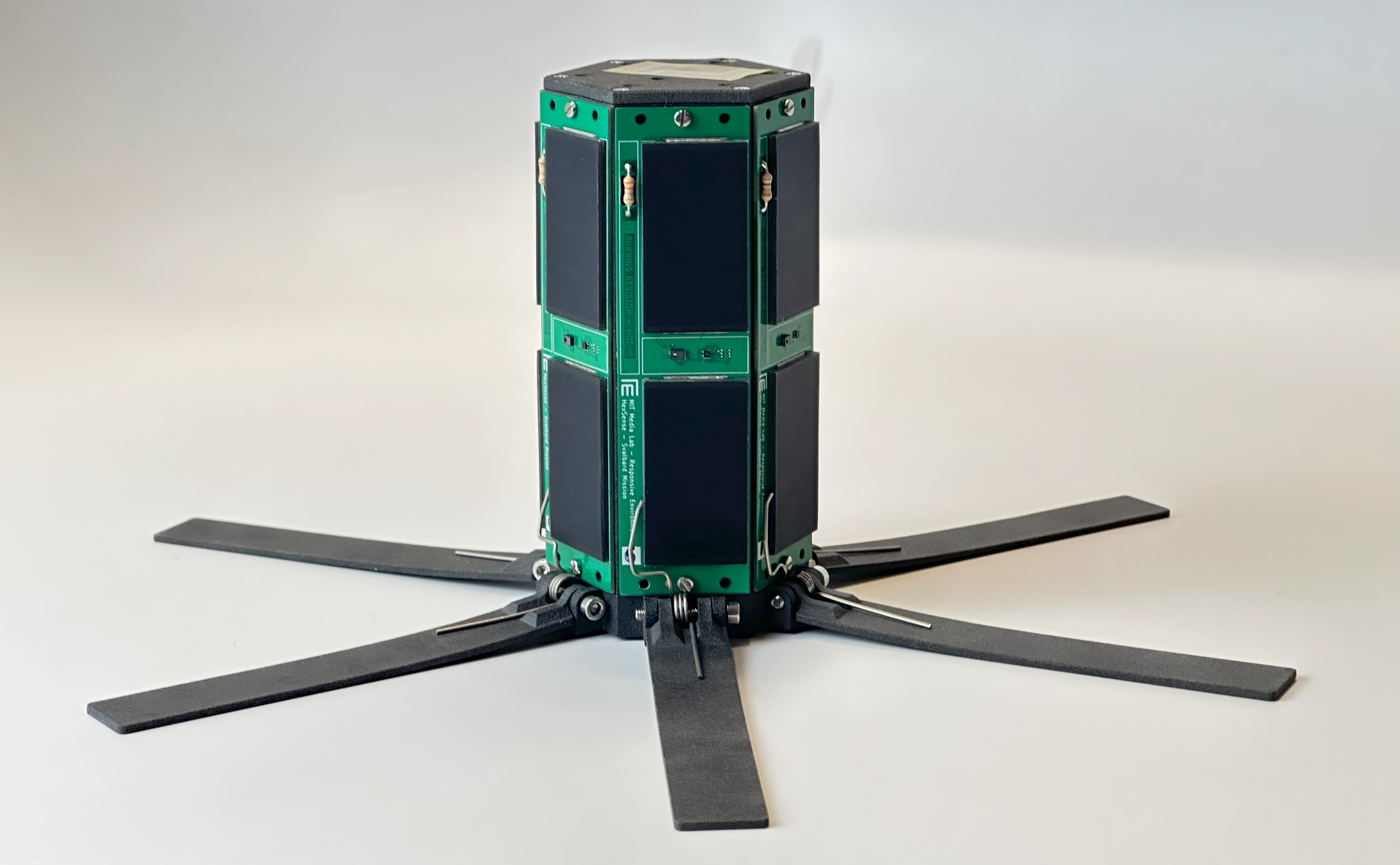

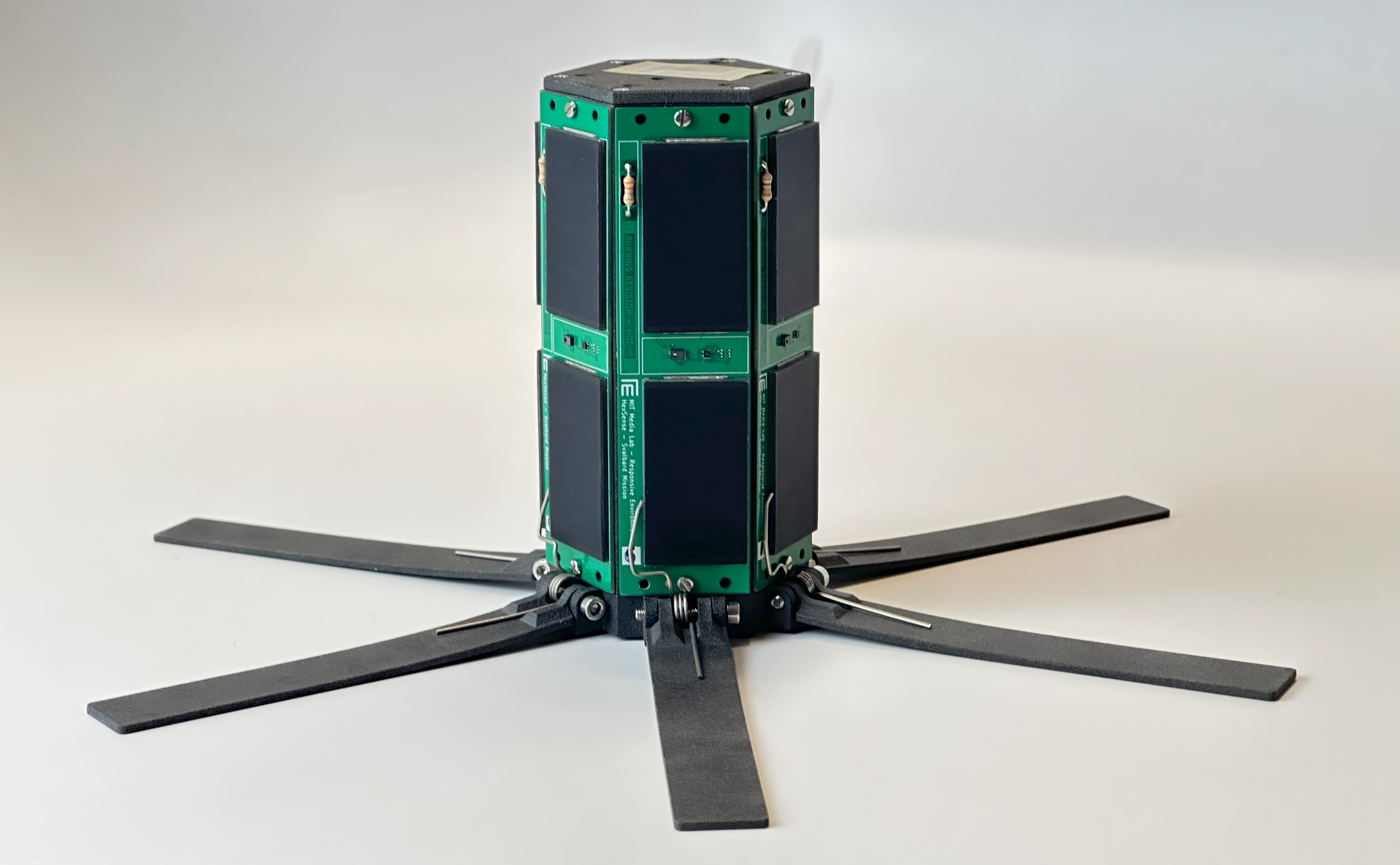

I designed this wireless sensor node,

named

HexSense, that can ballistically deployed from

a rover or lander to the Lunar surface.

After deployed and the HexSense landed, it will automatically stand up and start working.

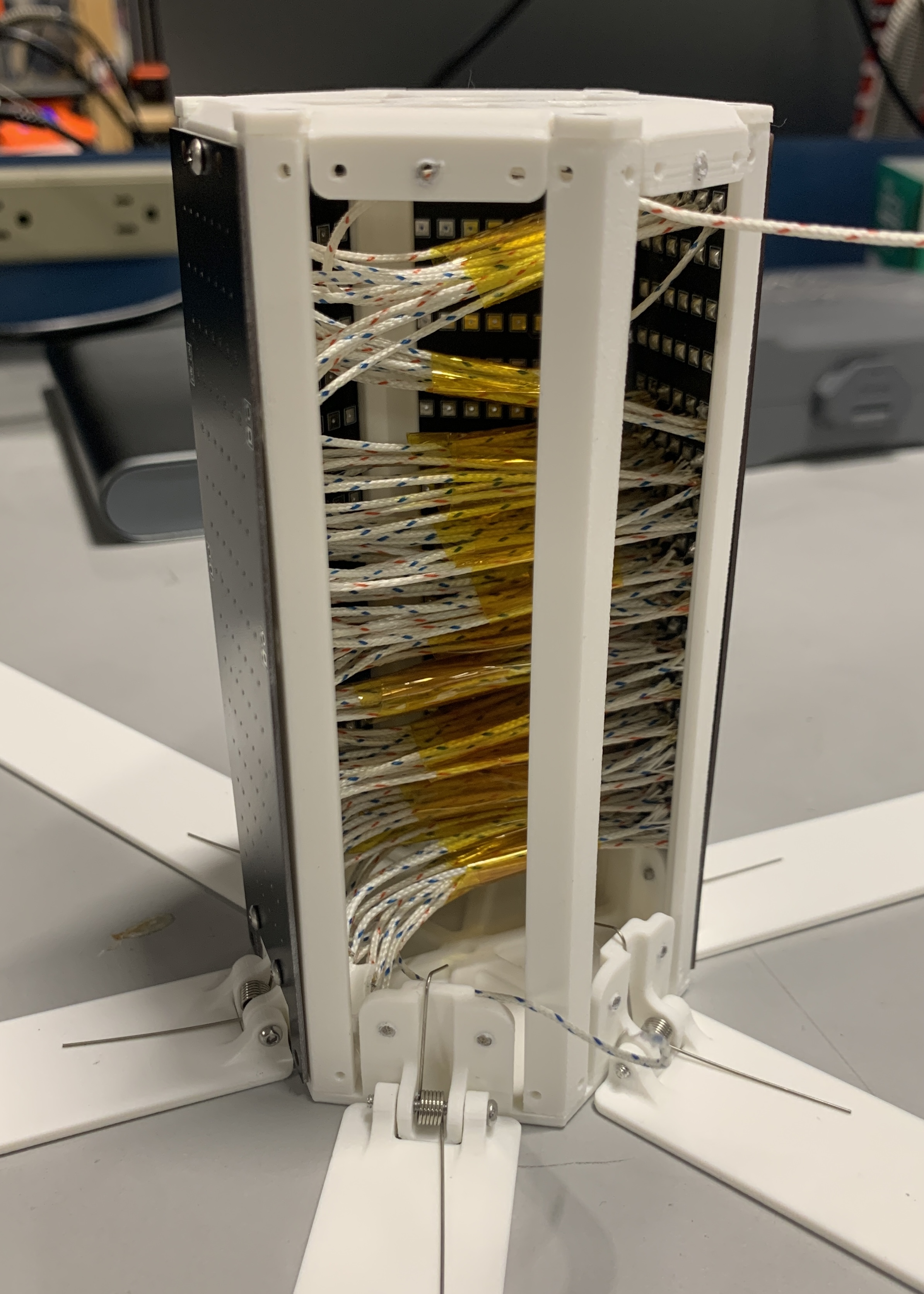

A HexSense sensor node

A HexSense sensor node

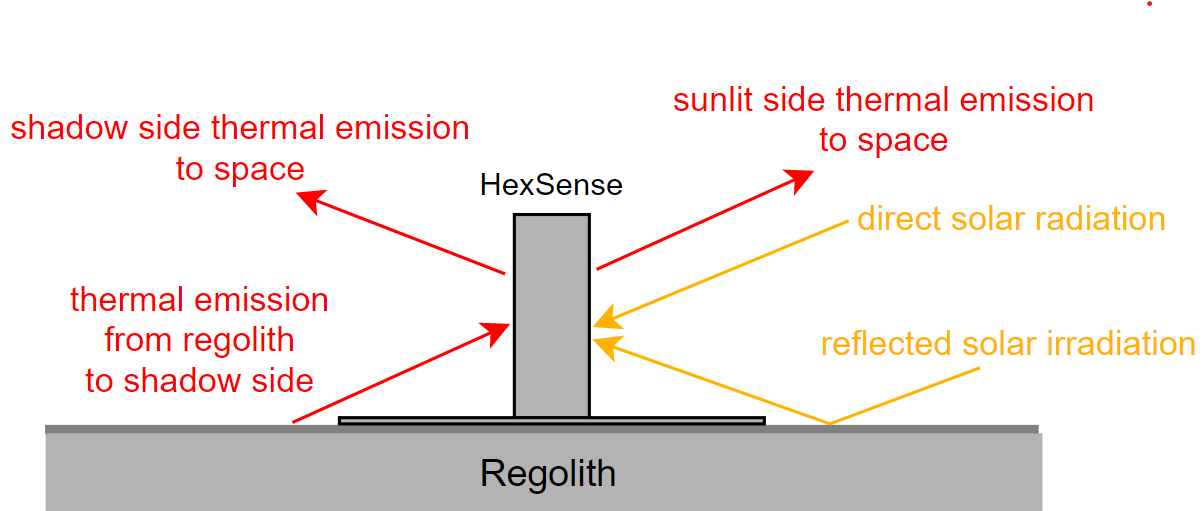

When working on the moon,

after the HexSense node starts working, one side will be facing the sunlight,

and the opposite will be in shadow. The temperature on the sunlit side is much

higher than the shadowed side. This will form a great temperature

gradient across the surface of the HexSense node. A thermopile can be used to

harvest energy from this temperature gradient.

Simulation

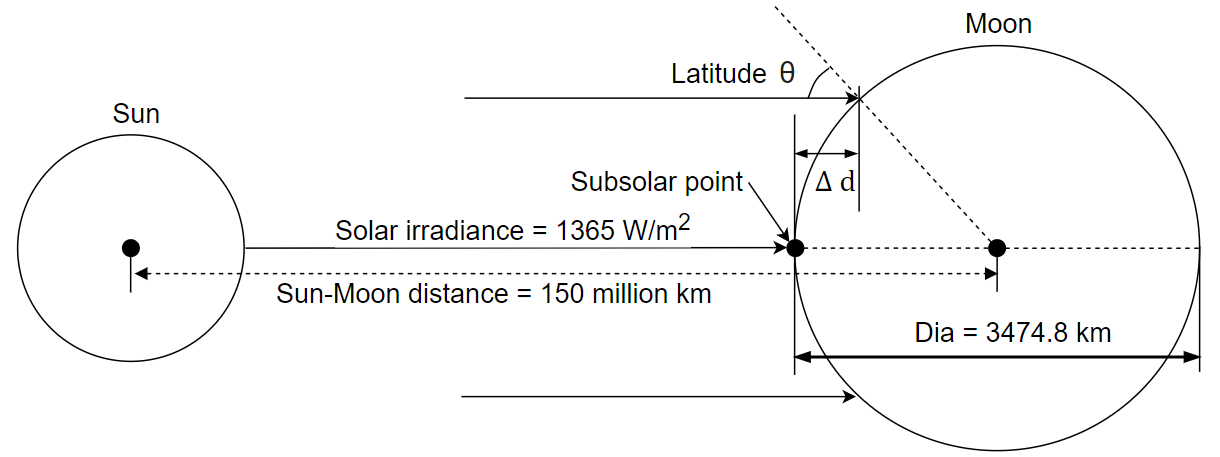

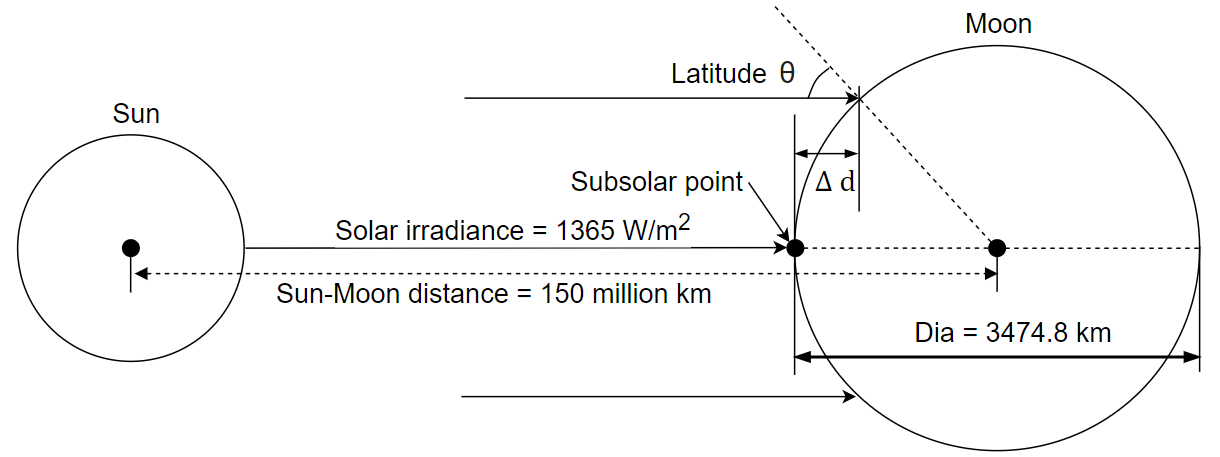

I set the position of the sensor node at a high latitude on the moon

since the Lunar polar regions are of great interest for future exploration.

In polar regions, solar irradiation has a big angle of incidence,

which means the sunlight is always low on the horizon,

therefore the Lunar surface temperature is low. However,

as the node is vertical to the Lunar surface,

the solar irradiation is almost perpendicular to the surface of the node,

which can efficiently heat the sunlit side of the node.

Schematic diagram of the Lunar surface solar irradiance condition.

Schematic diagram of the Lunar surface solar irradiance condition.

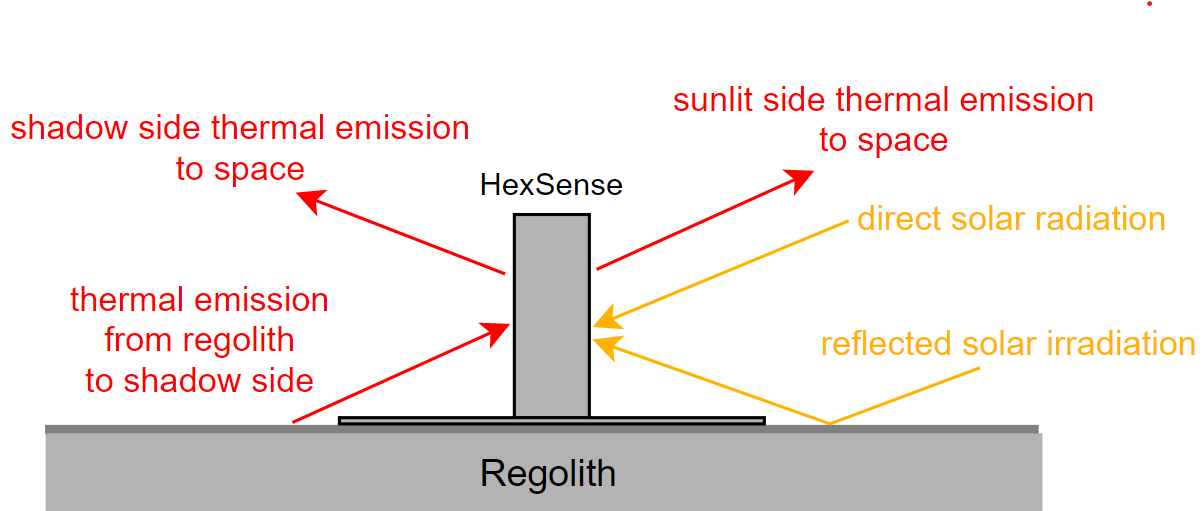

In the simulation, the thermal environment of the sensor node is set as follows:

The thermal environment the sensor node is in on Lunar surface.

The thermal environment the sensor node is in on Lunar surface.

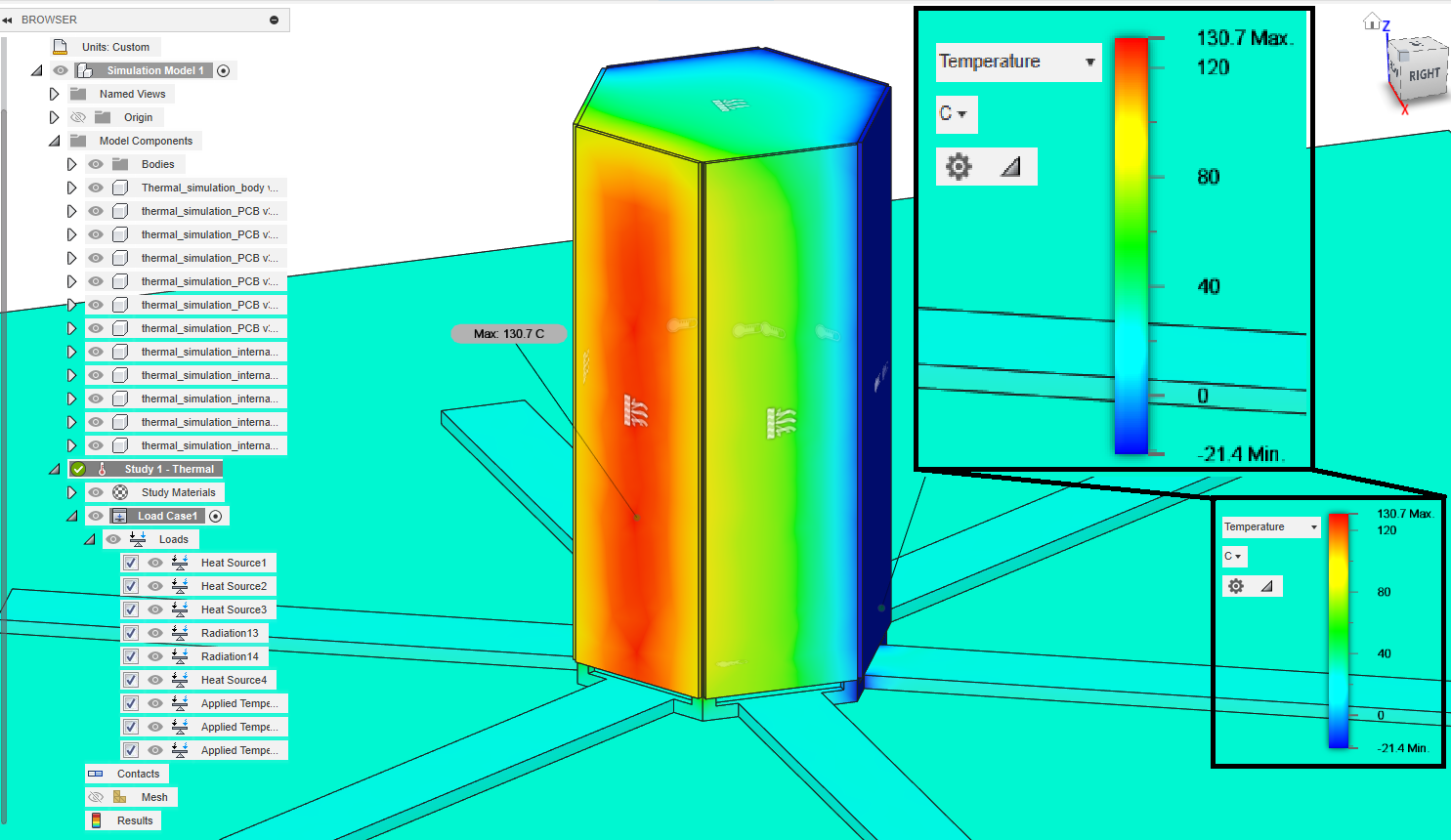

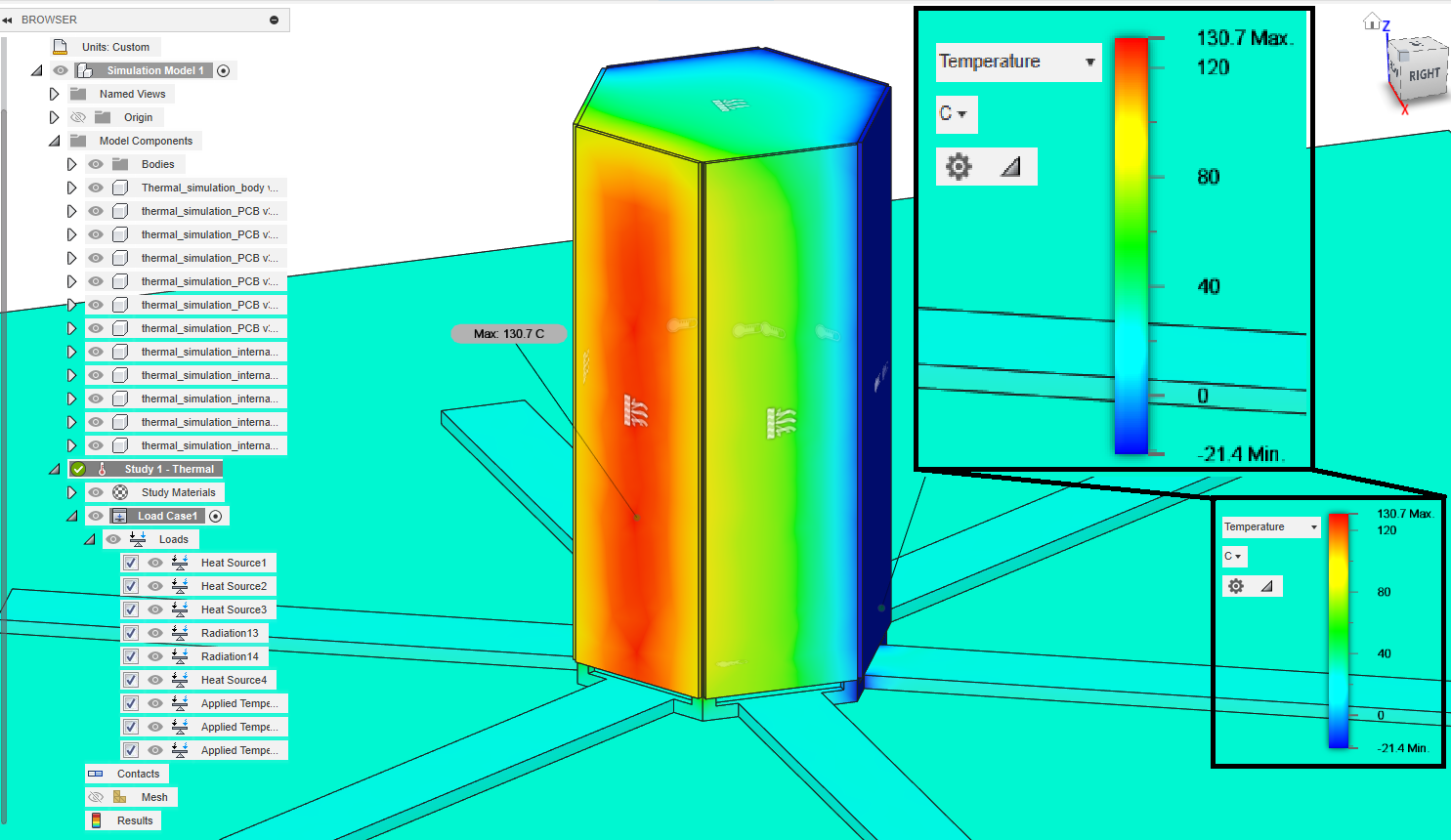

The simulation results are as follows:

Thermal simulation result of the sensor node on the Lunar surface.

Thermal simulation result of the sensor node on the Lunar surface.

The result shows that the temperature difference between the sunlit side and the shadowed side

can reach over 150 °C.

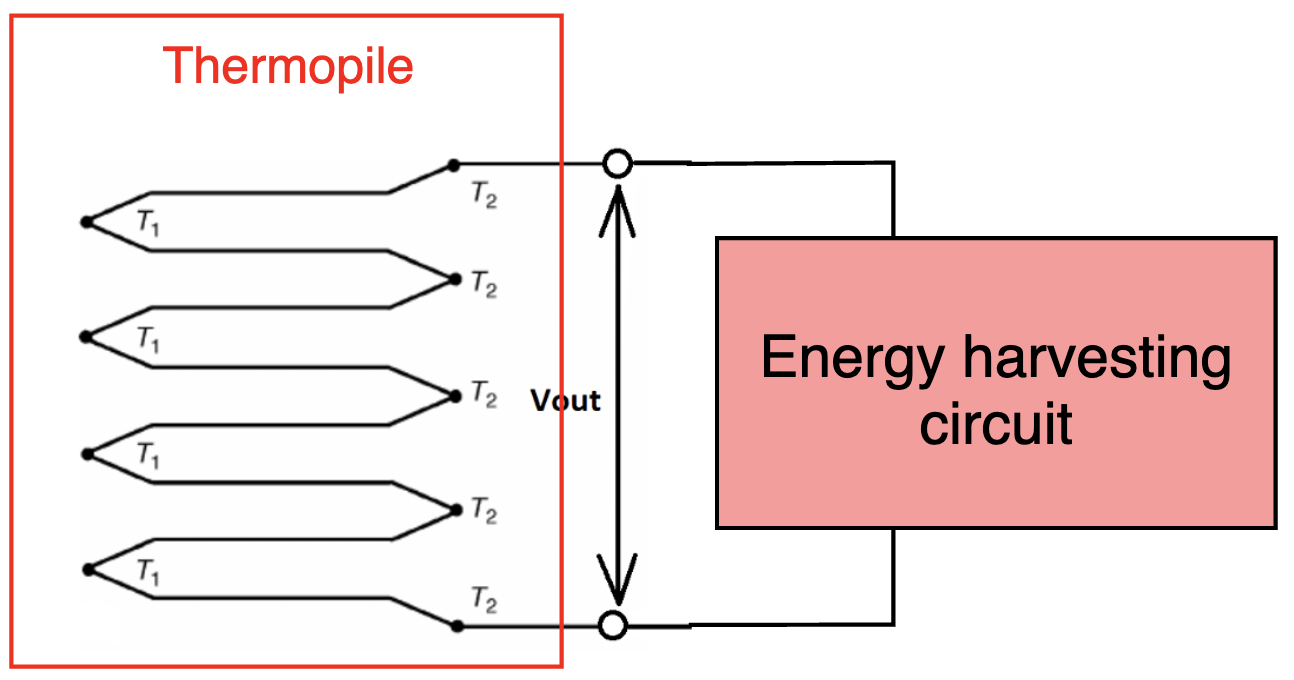

Energy harvesting system design

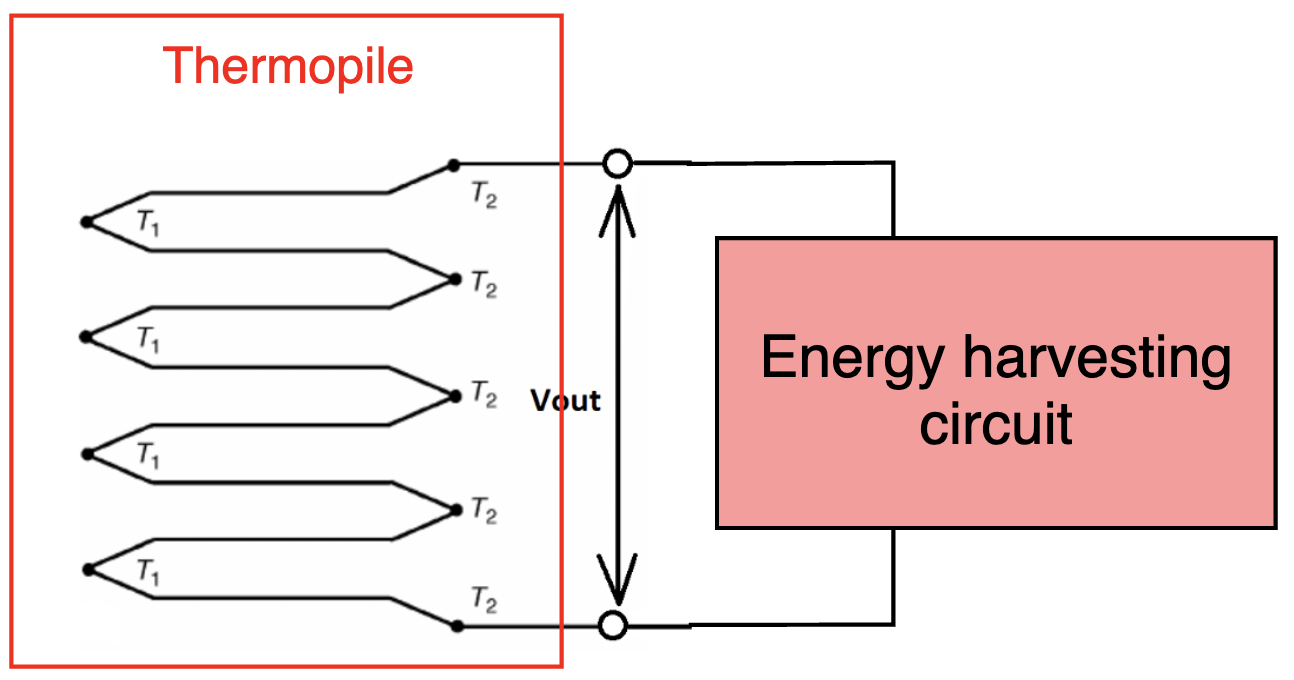

To harvest the energy from the great temperature difference,

A custom designed thermopile is used. The energy harvesting system diagram

is as follows:

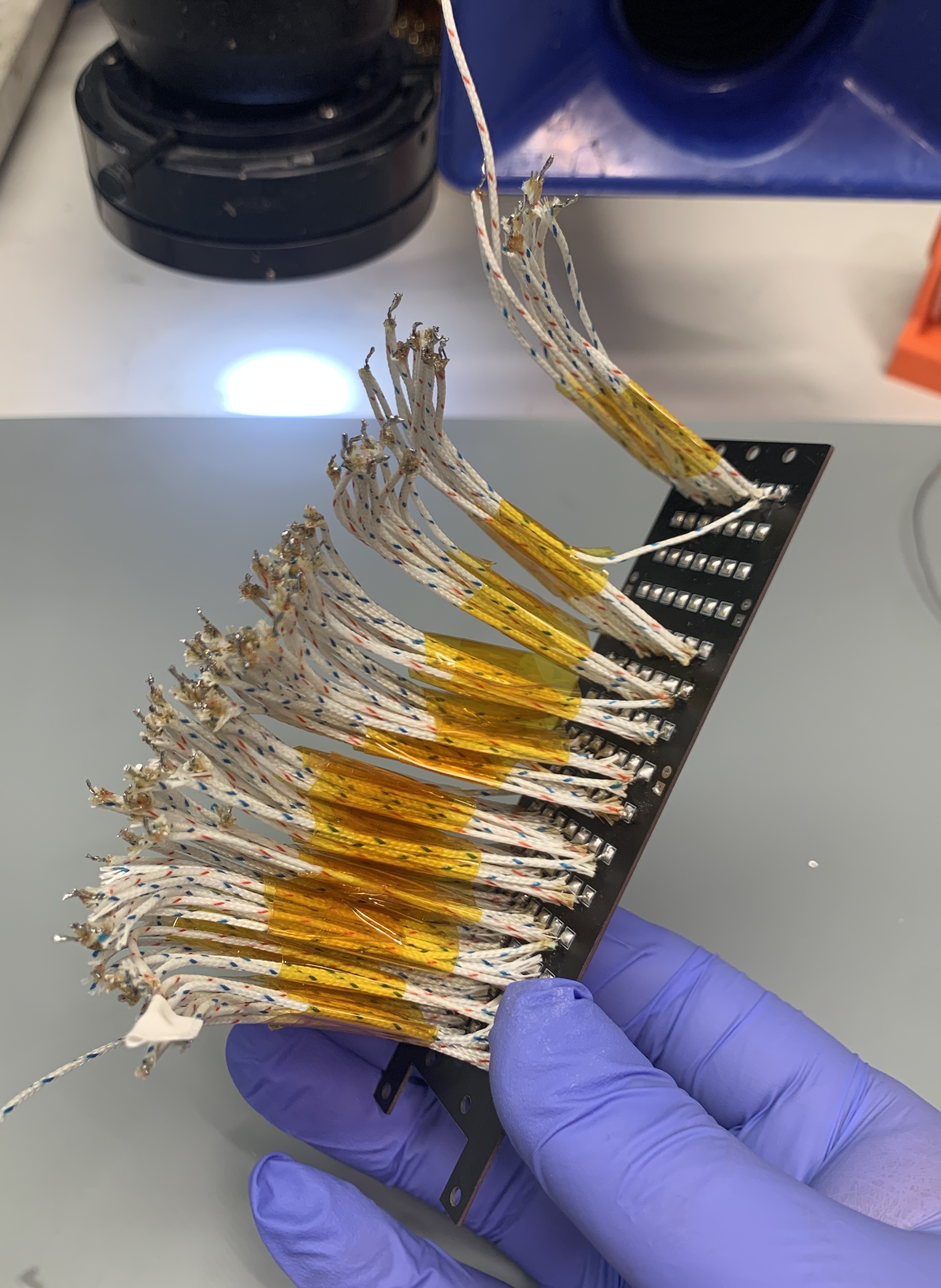

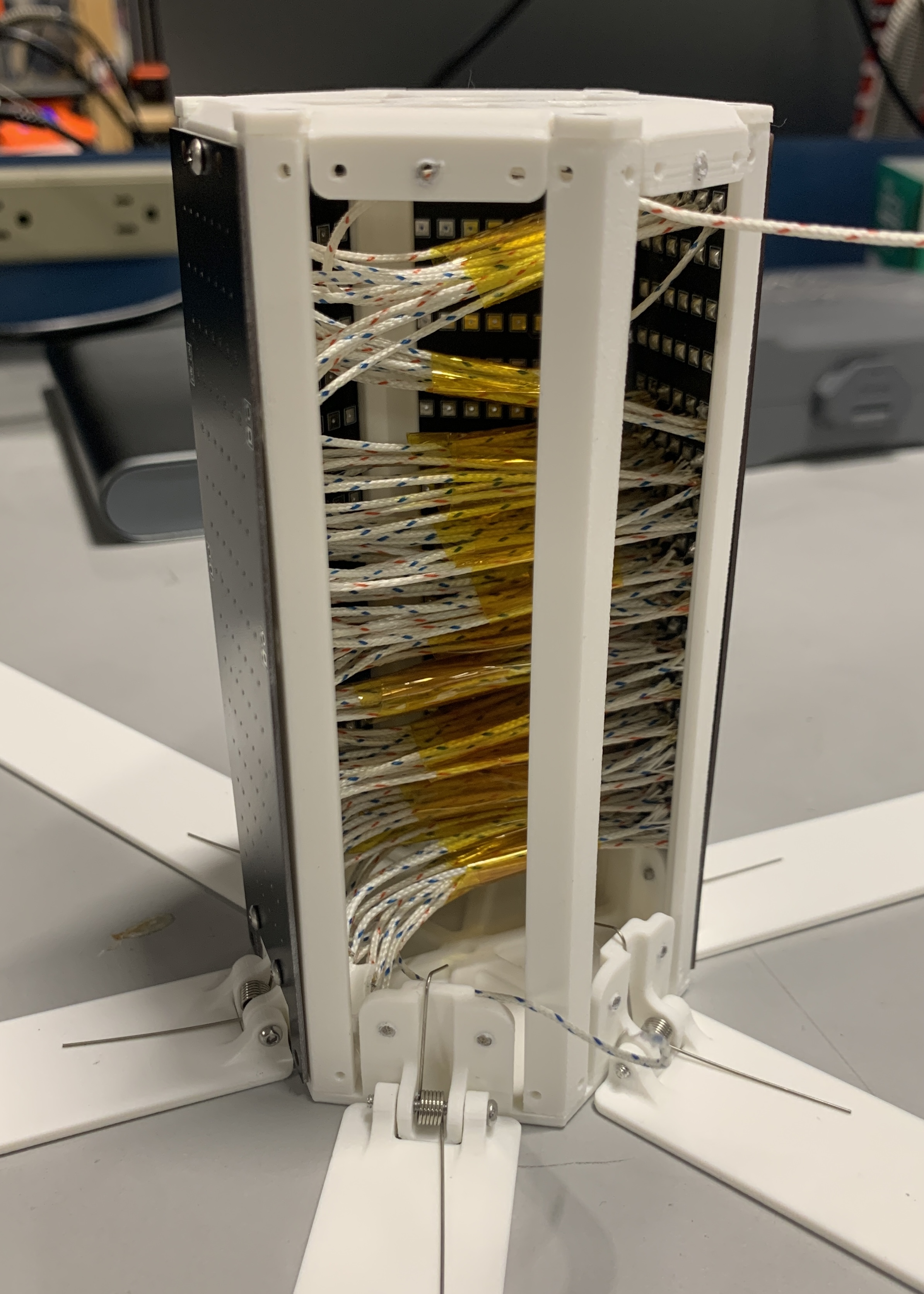

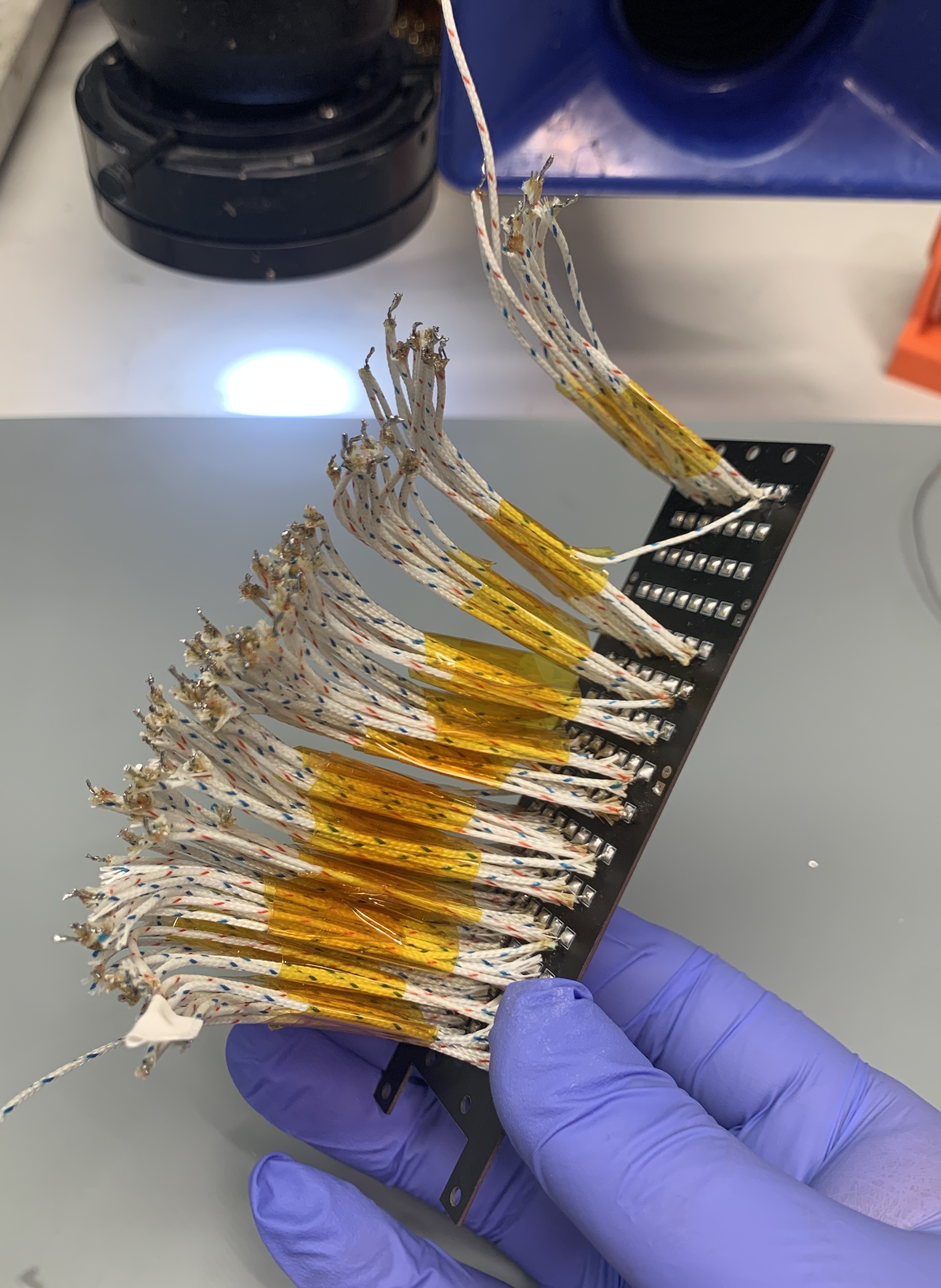

Energy harvesting subsystem diagram (left) the custom-made thermopile (right).

Energy harvesting subsystem diagram (left) the custom-made thermopile (right).

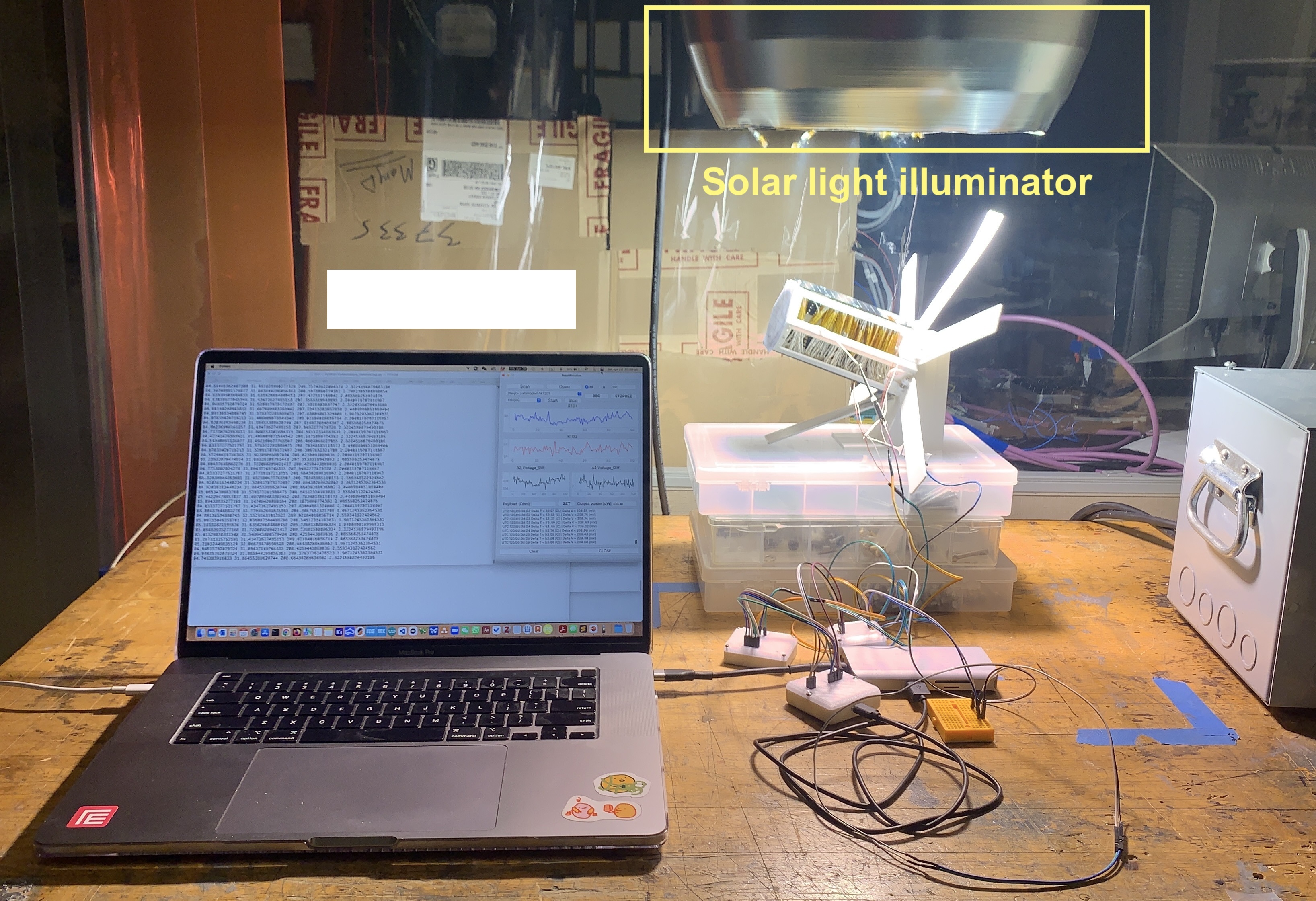

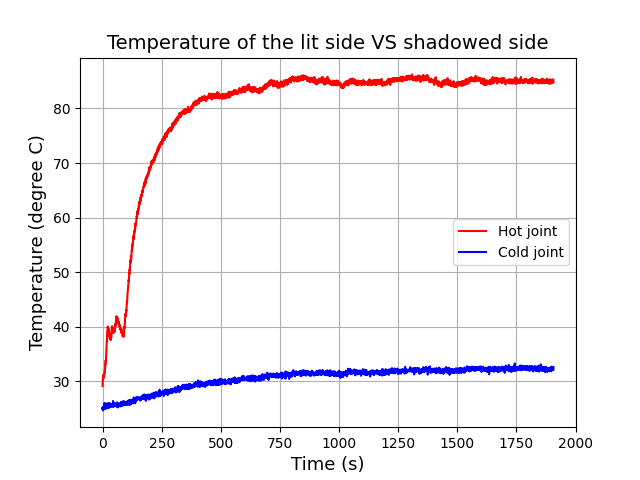

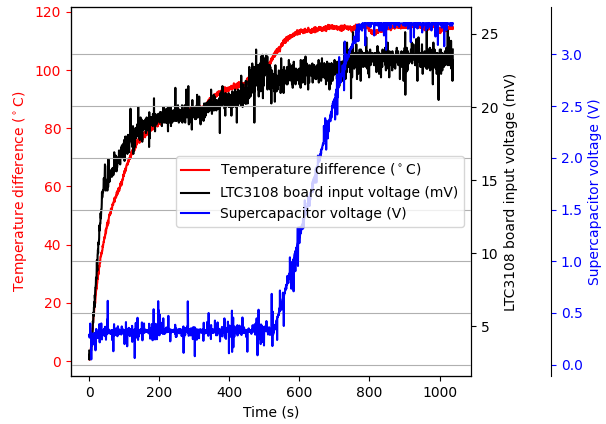

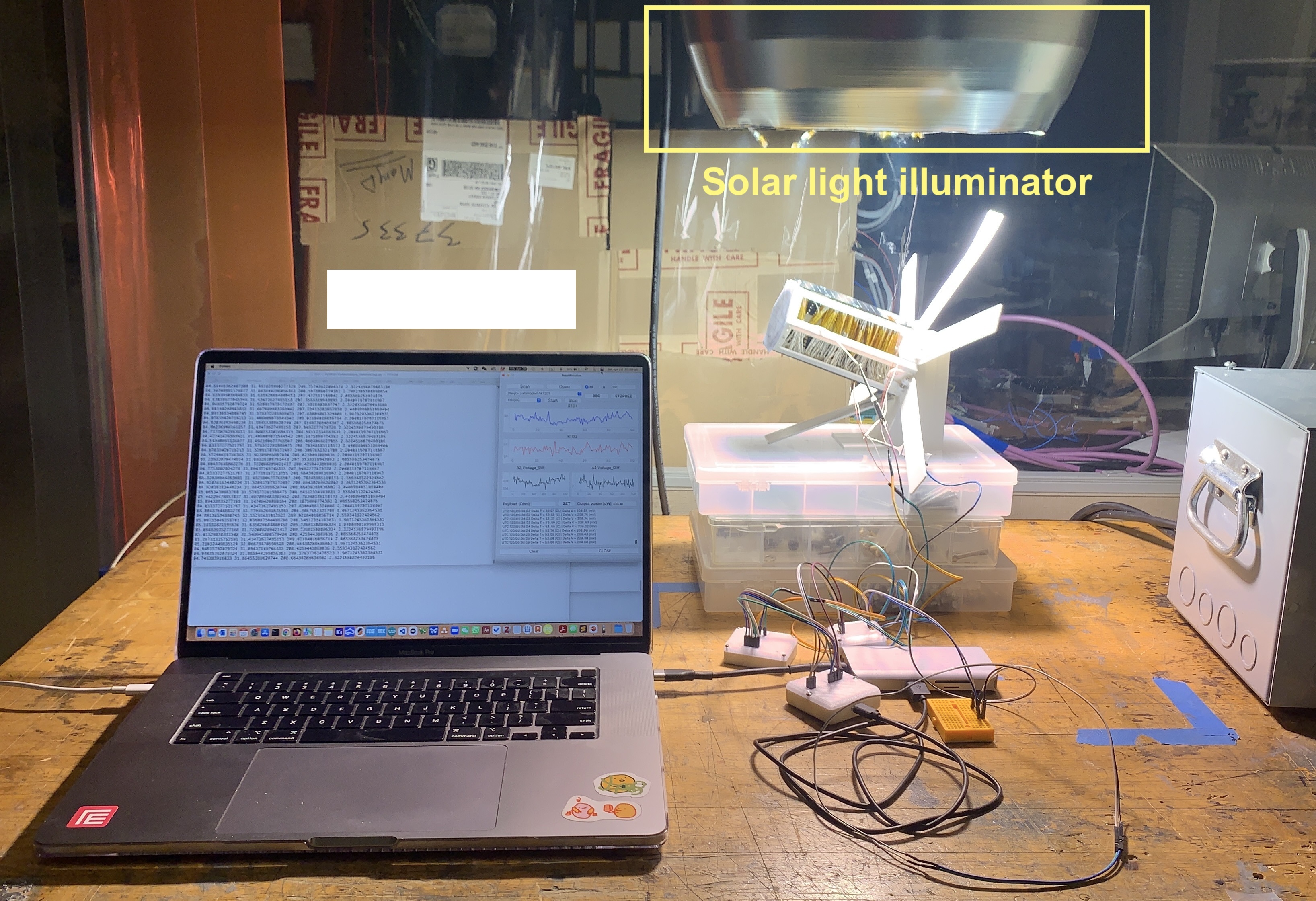

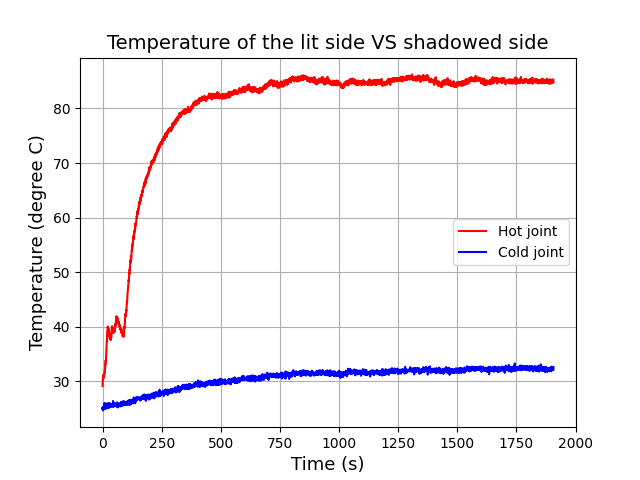

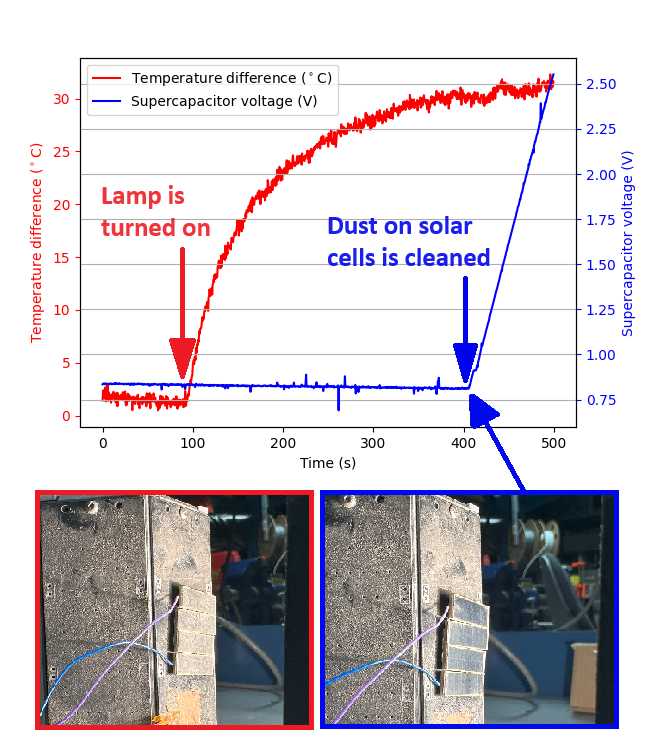

A lab experiment was conducted to test the temperature gradient formation,

and the results are as follows:

Lab experiment setup with a solar light illuminator (left)

The temperature changes on the lit side and the shadowed side (right).

Lab experiment setup with a solar light illuminator (left)

The temperature changes on the lit side and the shadowed side (right).

In the lab test, a 50 °C temperature difference was achieved.

As the lab experiment is limited, so it didn't get a

temperature difference as big as the simulation results.

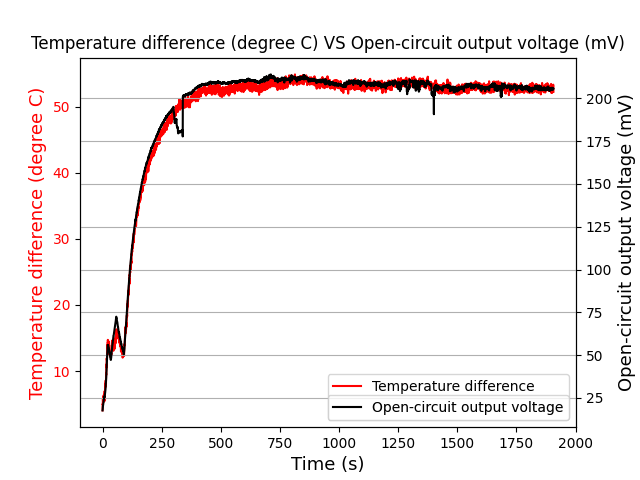

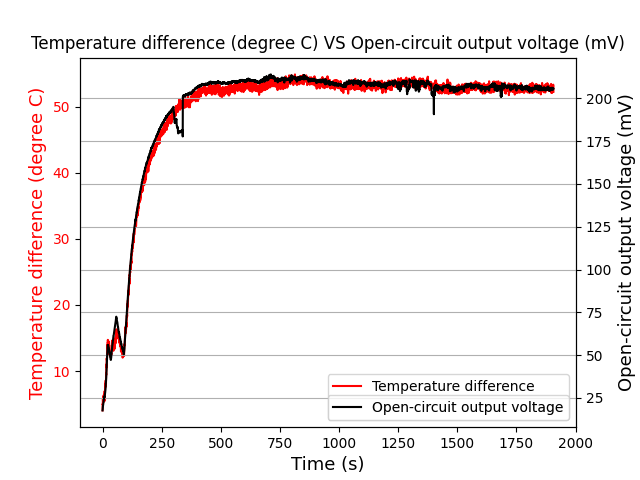

The open circuit voltage (OCV) of the thermopile is shown as follows:

The temperature difference and the open-circuit output voltage.

The temperature difference and the open-circuit output voltage.

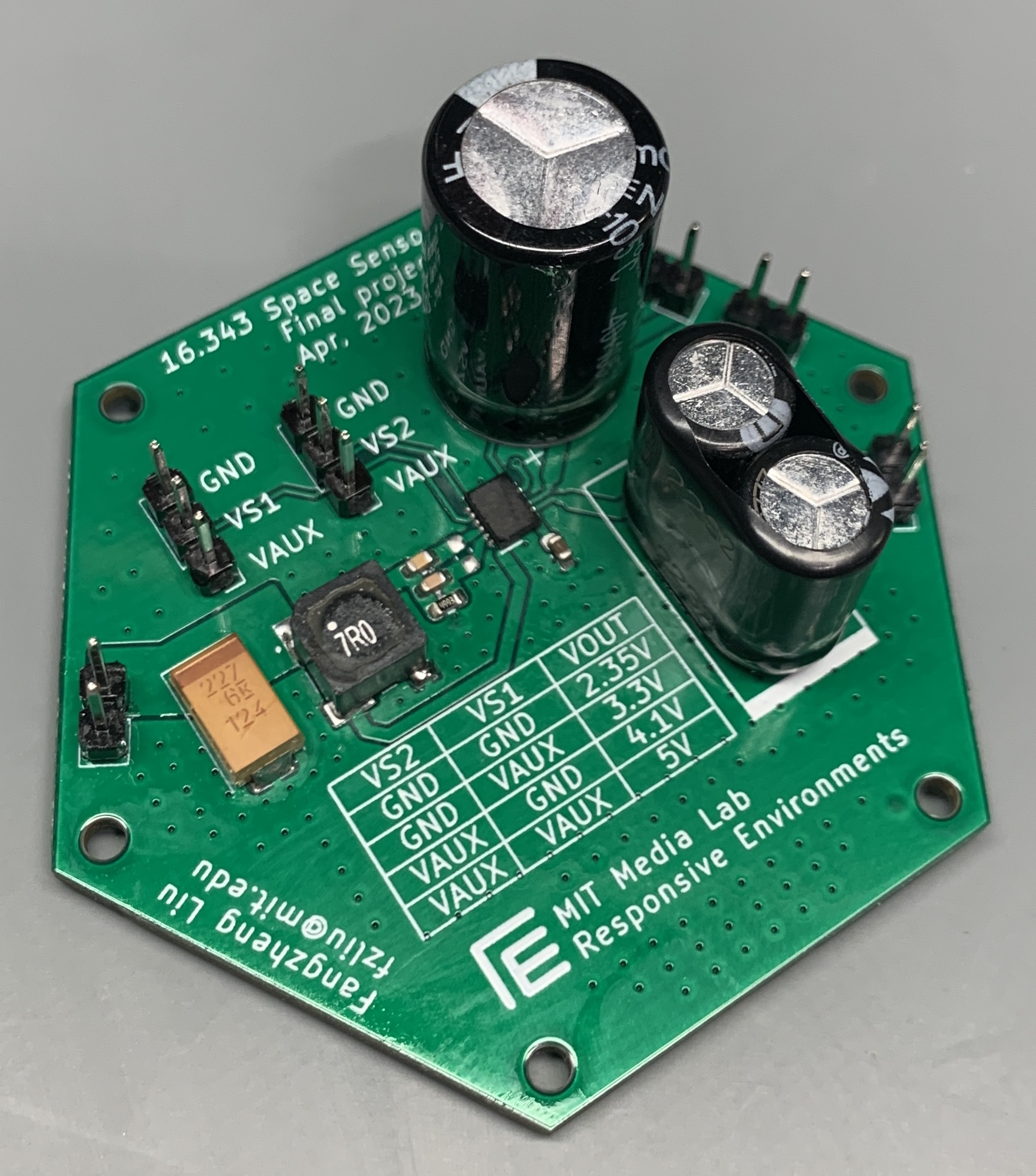

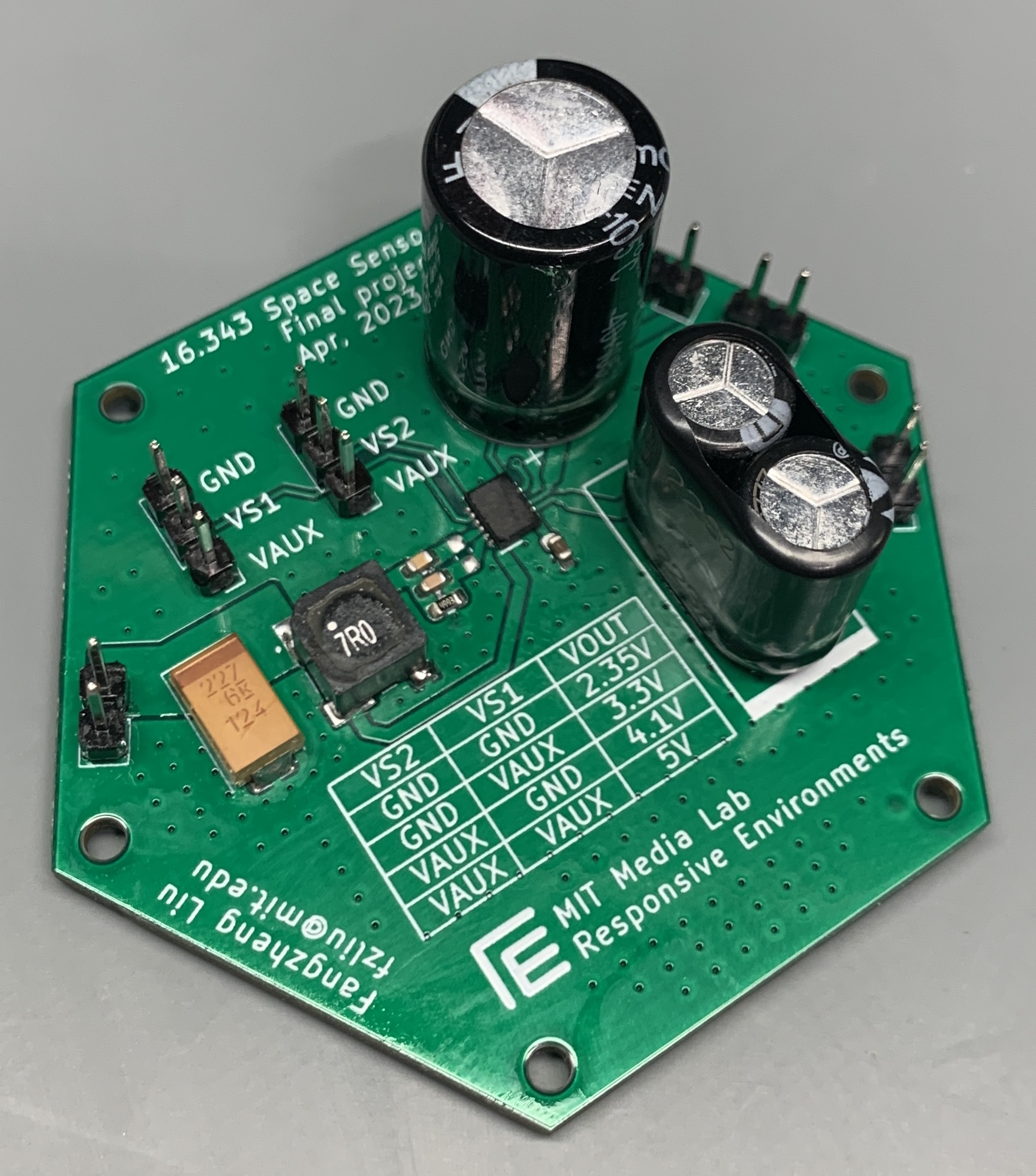

To harvest the energy from the temperature difference, a custom-designed

energy harvesting circuit based on

LTC3108 was used,

as shown below:

Custom-designed energy harvesting circuit.

Custom-designed energy harvesting circuit.

However, as the input resistance of the LTC3108 is too low,

which will reduce the thermopile output voltage when connected to the thermopile,

a higher temperature difference is needed.

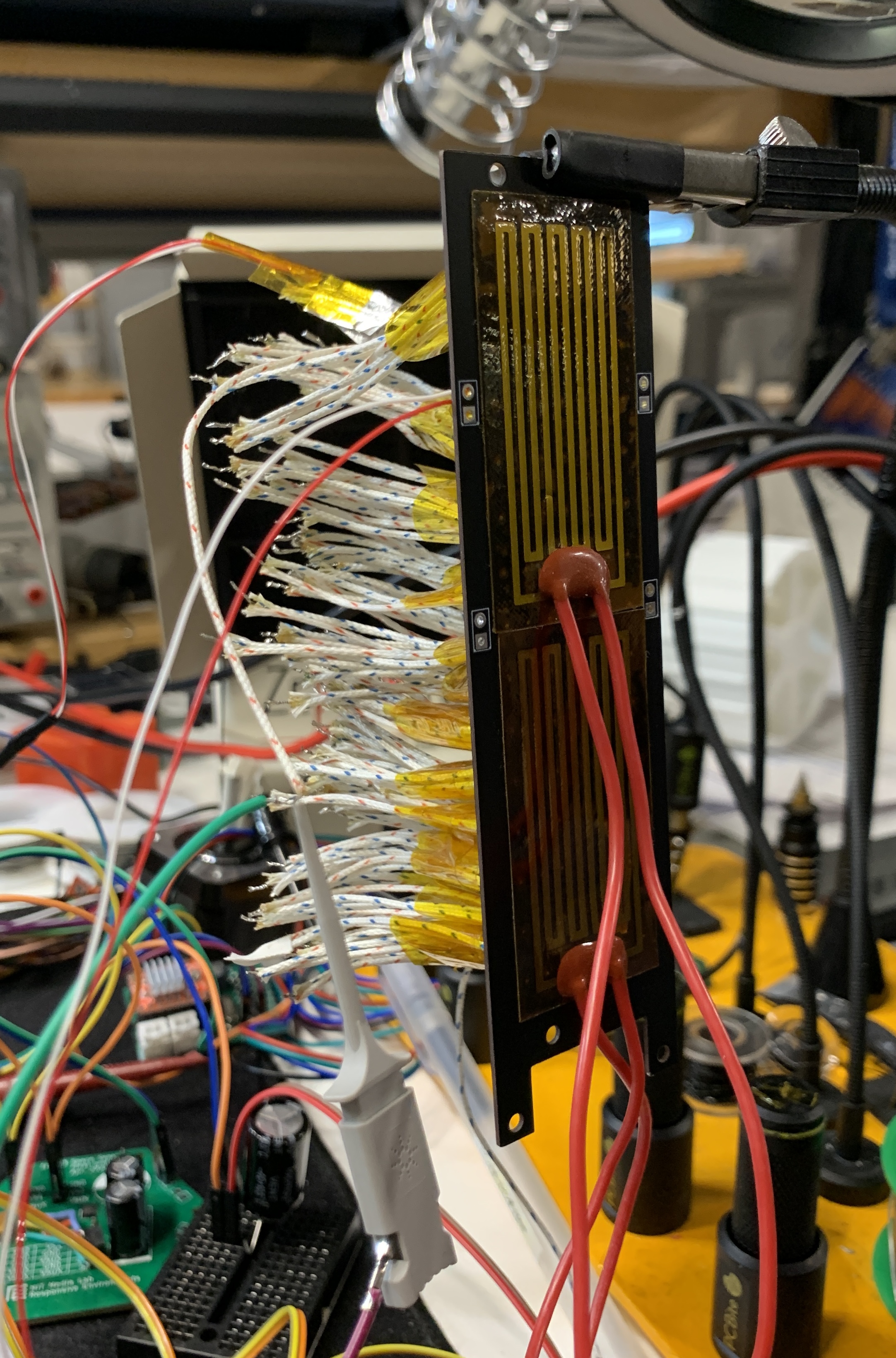

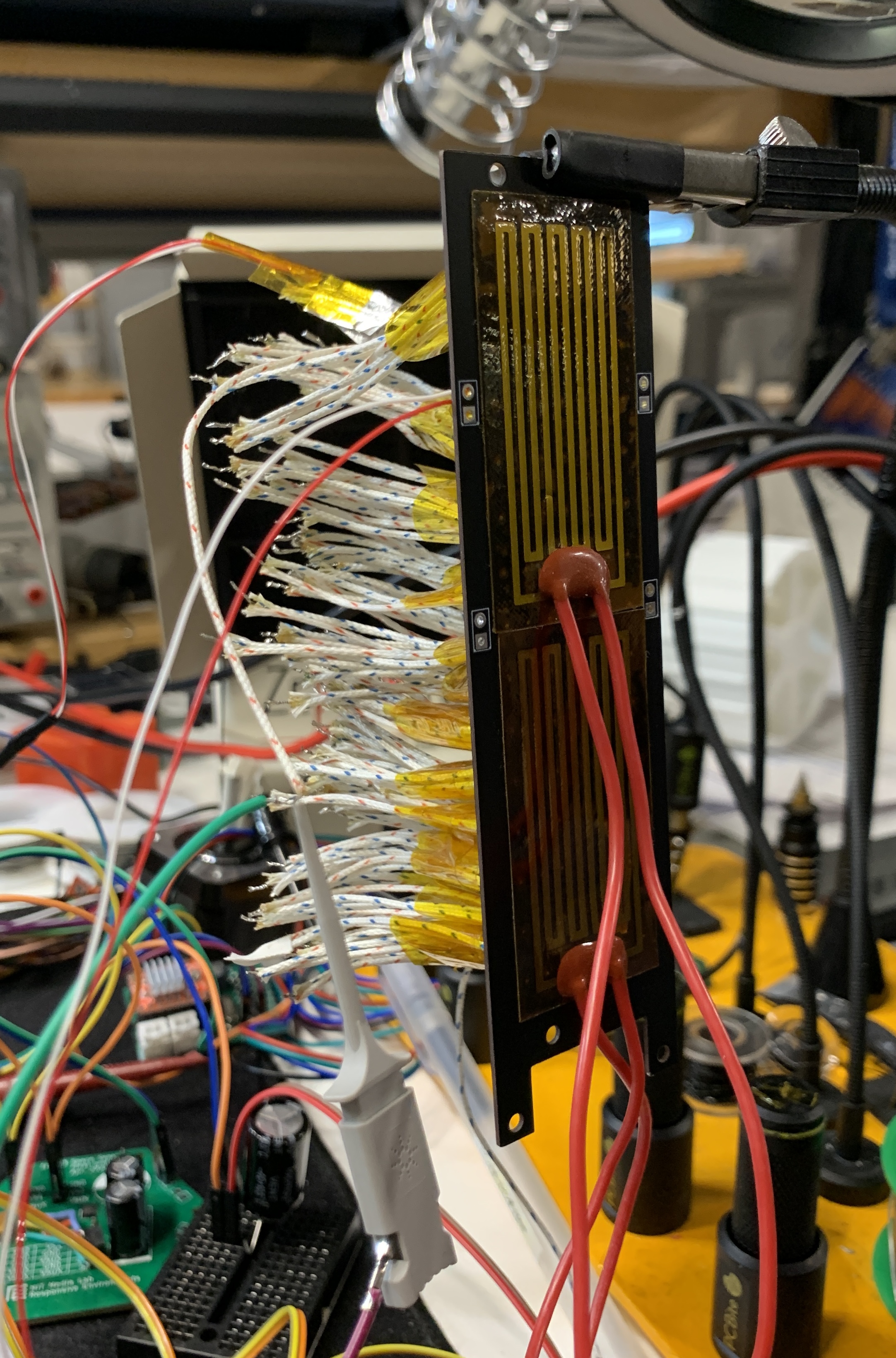

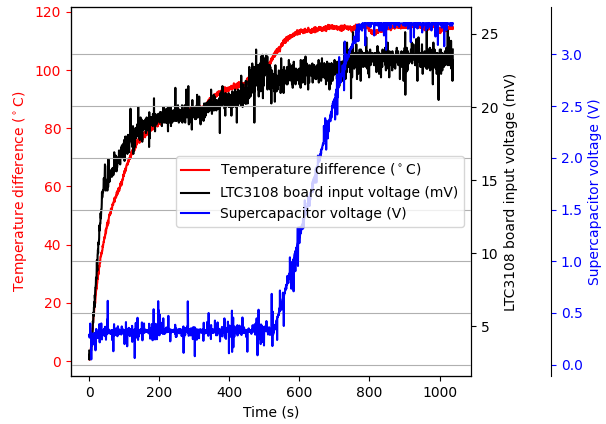

To achieve this bigger temperature difference,

two flexible heaters are used to heat the sunlit side of the sensor node.

Two flexible heaters are attached to the node

side where the thermopile hot joints are attached (left)

result from the experiment with heaters

attached to the hot joint side (right).

Two flexible heaters are attached to the node

side where the thermopile hot joints are attached (left)

result from the experiment with heaters

attached to the hot joint side (right).

The results show the energy harvesting circuit is successfully triggered

and started to harvest and store energy in an electrolytic capacitor.

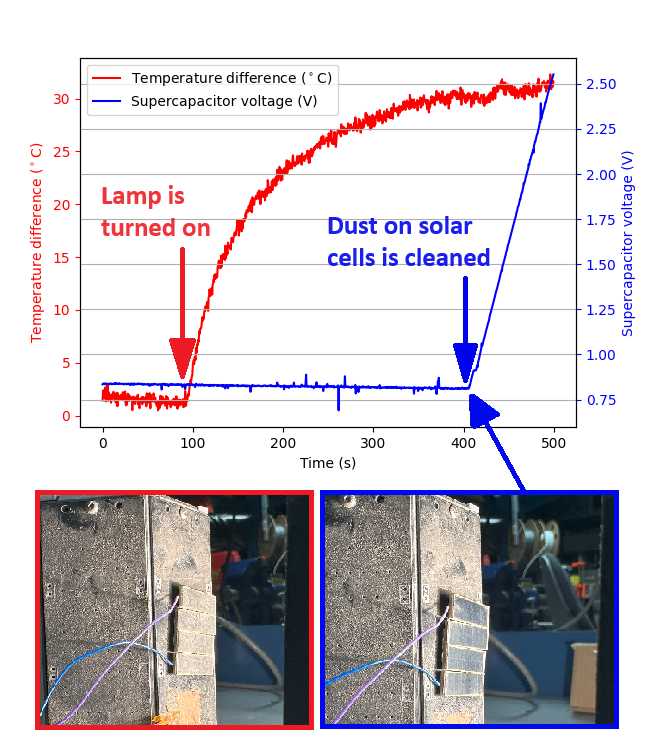

The performance of our approach and solar cells is also compared.

One big advantage of this approach compared with the solar cell is:

the solar cell can not work in dusty environment, but the temperature

gradient can still be formed with a layer of dust covered. Therefore,

with a better thermopile designed, this approach can still harvest energy

in a dusty environment such as the Lunar surface.

Solar cells can not work with dust covered. The temperature

gradient can still be formed with a layer of dust covered.

Solar cells can not work with dust covered. The temperature

gradient can still be formed with a layer of dust covered.

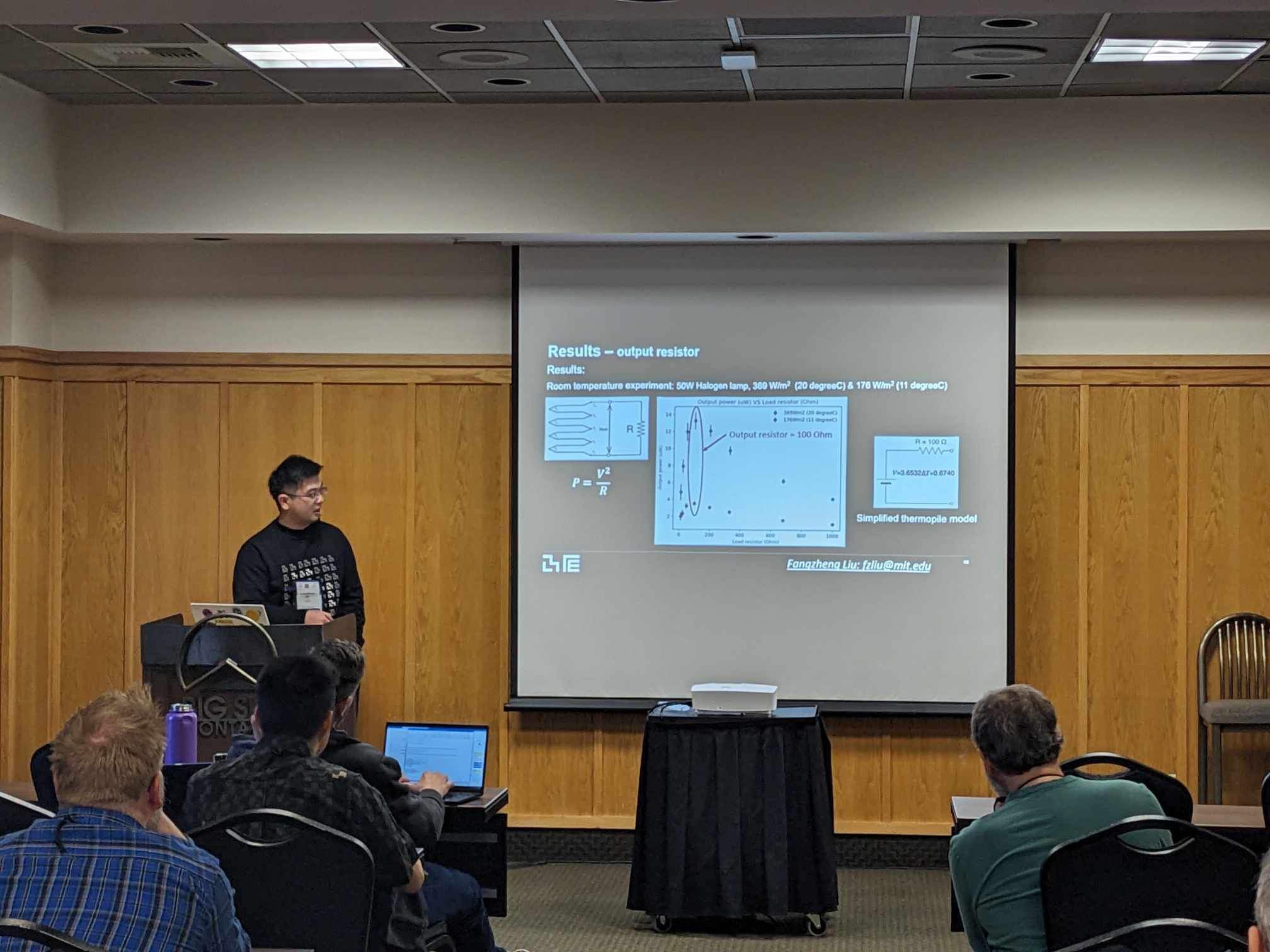

Presenting the paper at the IEEE Aero Space Conference 2024.

Presenting the paper at the IEEE Aero Space Conference 2024.